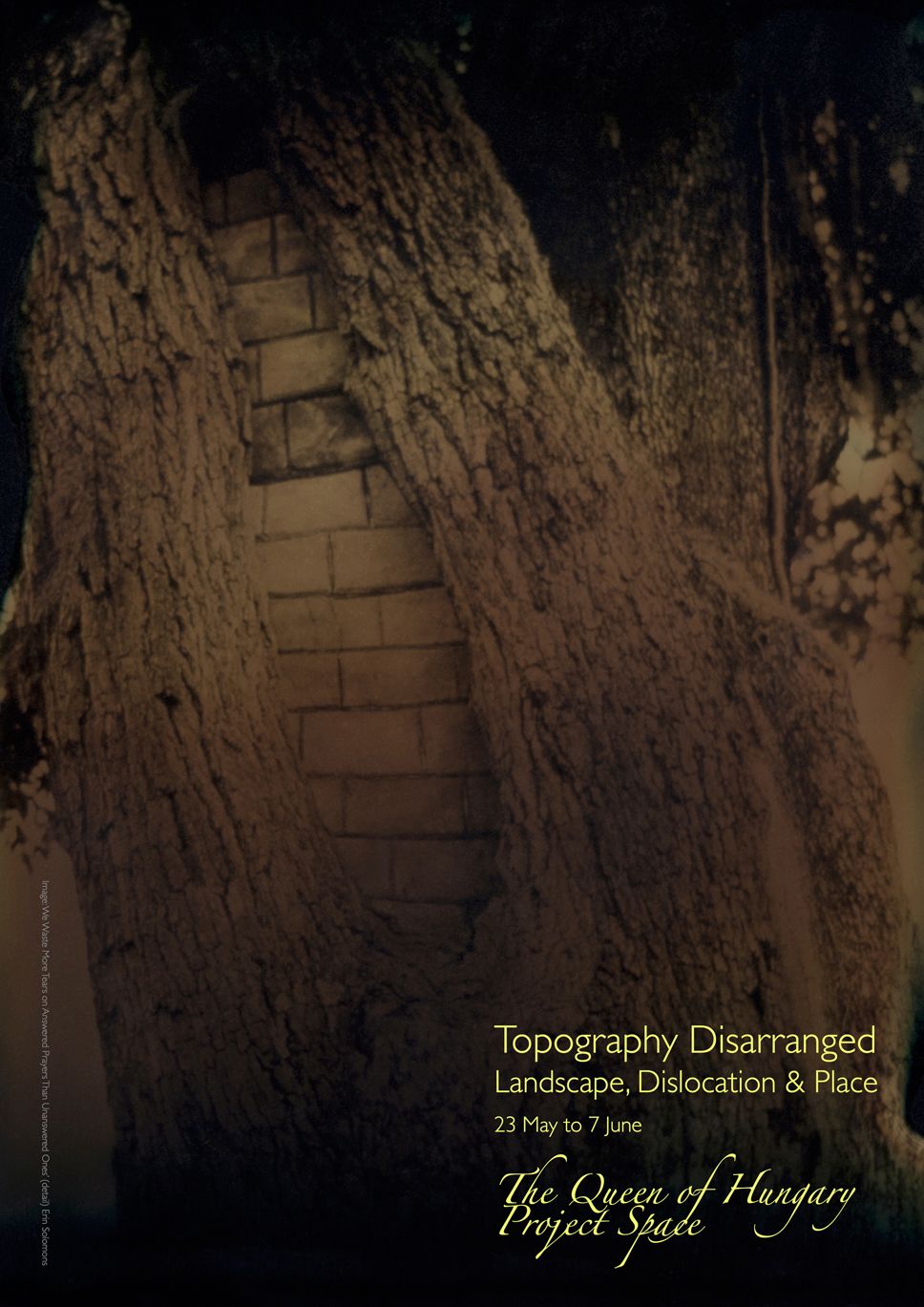

TOPOGRAPHY DISARRANGED: Landscape, Dislocation & Place

23RD MAY - 7TH JUNE 2014

Selected by Paul Fieldsend-Danks, Eliza Gluckman and The Queen of Hungary Project Space

Judith Stewart info

Project Space Blog

Judith In-Conversation

June 5th 7pm

TOPOGRAPHY DISARRANGED: Landscape, Dislocation & Place23RD MAY - 7TH JUNE 2014 |

Selected by Paul Fieldsend-Danks, Eliza Gluckman and The Queen of Hungary Project Space |

Events | |||||

|

Judith Stewart info |

Projects | |||||

Project Space Blog |

Classes | ||||||

Judith In-Conversation |

About | ||||||

June 5th 7pm |

Contact | ||||||

|

|||||||

Some Thoughts On Landscape |

||

We have a tendency to expect contradictory things from landscape. On the one hand we ask it to embody notions of belonging, of home and identity - attributes that could be defined as 'place' – whilst at the same time, as 'space' it suggests emptiness, a void that opens up possibilities for an expansion on which to project our own longings. However, both of these ways of thinking about landscape imply and rely upon a position of looking on from an outside. The very term 'landscape' already puts us in a position where, as with the sublime and picturesque, what we experience is a concept, an ideology, rather than the physical phenomena we think it is. With this in mind, we seek out the landscapes best suited to our own internal desires and project these upon real spaces. It is a truism that today most of us are dislocated from a relationship with the land, yet many of us dream of the possibility of a reconnection that will bring something more immediate and 'real' into our lives. Having been removed from a relationship of direct dependency, our experience of the land – the physicality of a place rather than a view – is limited to its visual qualities or to attempts to re-establish connections through gardens and allotments. Even the latter cannot avoid the sharp reminder of our outsiderness, brought into sharp focus when we encounter those whose bodily rhythms and experience of time is felt through their connection to a particular place. Part of us continues to mourn this loss. In Of Other Spaces: Heterotopias, Foucault proposes that ‘…the great anxiety of our era has to do fundamentally with space…’ He goes on to suggest an alternative to the utopia/dystopia dichotomy so frequently applied to space or place, proposing instead the existence of spaces that can simultaneously hold different, even contradictory, meanings – heterotopias. Such spaces and places can be both physical and imagined, but are also ‘real sites that can be found within culture’ which are ‘represented, contested and inverted.’ Foucault may be correct in pin-pointing ‘anxiety’ as the dominant emotion in relation to space. We are anxious for particular places: anxious to maintain enough personal space, made anxious by space, and whilst many of these anxieties are beyond our control as individuals, we attempt to alleviate them by finding (or creating) our own physical and psychological spaces – to belong; to have our own space. I am tempted to go further and to suggest that there are no longer any sites that are not contested and that this is precisely because they have all become, to some degree, imagined. Thus it could be said that all sites have become disarranged by our own sense of dislocation. Foucault’s notion of heterotopia, embracing as it does ideas of place as contained entity, as incompatible multiple spaces, or as a marker for what lies outside, provides us with a way of thinking about place that can address many of the current debates involving landscape, place and contemporary practice. East Anglia, the region where this exhibition is sited and the landscape with which I am most familiar, itself embodies a variety of anxieties. Making the inner workings of one's head into images involves wrestling with the weighty legacy of landscape that has previously been divided (rather like the Cartesian subject) into the Romantic sublime versus pastoral beauty. East Anglia sits uncomfortably between the two - a subject who will not be divided - conforming neither to the 'masculine', rugged, sublime nor the 'feminine' idyllic, pastoral beauty of the English countryside that inhabits our imagination. Its undramatic landscape is not only the very antithesis of the sublime landscapes long favoured by artists, being flat and intensively cultivated, it is also very un-pastoral. Most of the region is highly regimented and controlled: dominated by industrial agriculture. The small mixed farms have all but disappeared, and have been replaced by a monoculture of potatoes, sugar beet, rape and barley – the very embodiment of agri-business. Yet, like other rural areas, parts of East Anglia remain desirable destinations for Londoners in pursuit of the rural idyll. Lured by the openness, it is imagined that this must mean the possibility of space and freedom, yet in reality much of that space is inaccessible as farmers and landowners tend not to support the right to roam. So forays through the countryside are confined to set routes on the legal footpaths (which may be blocked for weeks because of the hazards posed by the spraying of potatoes with sulphuric acid), or involve braving the dangers of rural roads. Away from industrial production, the wilder areas have have been tamed and packaged for the tourist industry in a desire to make the countryside 'accessible' and diversify flagging rural economies. Clean, level boardwalks take the day tripper over areas that ought to be inaccessible, and treacherous, muddy trails are flattened, dried out and pavemented. We look at rather than inhabit the space and realise that the sublime is hard to encounter. The wildest areas are now often those least regarded and overlooked spaces on the outskirts of urban sprawl. While much of the region is highly controlled, at the edges it is rapidly slipping away – literally – and I experience another sort of anxiety, being constantly aware of the places that are now submerged. Attempts to control the effects of the sea are not only ugly but futile, and it is something between the relentless wetness around the edges combined with the inhospitable interior that makes the whole place seem poised on the edge of destruction. This disappearance is not only happening at the edges though. On the occasions when I attempt to navigate the areas I once knew well, I wind up getting hopelessly lost as all the expected landmarks have disappeared in a sea of identikit estates and tarmac. And I am in danger of wallowing in nostalgia. Whilst the physicality of specific locations are significant to the artists in Topography Disarranged: Landscape, Dislocation and Place, the varied responses underline the role of the imagined, emphasising the ideological and cultural nature of our responses. The practice of Marianne Holm Hansen, where the very fabric of particular places becomes the work, puts us in mind of common rituals undertaken in order to preserve and give a physical presence to memory: I am thinking here of the collection of a pebble from a beach, the pressing of a flower or the digging up of a lump of turf from a football pitch. Such acts embody the projection of our imagination onto place, returning us to the times when fragments of relics had real power. This physicality is an important element in Jaimini Patel's One Green Bottle which points to normally unseen, microscopic changes that shape spaces, and the location of the Queen of the Hungary itself becomes the subject for Oliver Payne, whose sound recordings hold the memory of the site at a particular point in time. For many of the artists here it is the everyday and overlooked that draws attention, building up a sense of what is or is not valued. Tim Simmons' large photograph, by drawing attention to apparently insignificant details, makes us question what it is we should be seeing or what we may be missing whilst Declan Woods uses the residue of the agricultural processes to change the flat Norfolk landscape into a mountainous region, thereby creating a space that is both real and imagined. It is important to remember that, for many of us, the urban is also a landscape on which we project our desires. Amy Prebble and Keef Winter, also focussing on the overlooked, both remind us of the relationship between the urban and rural by placing human experience and intervention centre stage. This human element, as we become familiar with the rhythms of particular urban spaces and then seek out cities in order to refresh our jaded palates is present in Erin Solomon's work which draws a parallel between the individual identity of trees and the individuality of humans. This work, with its referencing of a particular location, or 'place' heightens our awareness of the contradictory meanings attached to landscape when seen alongside Laura Napier's All the Places I Have Been, All the Things I Have Seen, in which places are collected like trophies in order to demonstrate to others (and ourselves), our open-mindedness or our adventurous nature. The range of works in Topography Disarranged demonstrates the continuing pull of landscape as a contested site for contemporary artists. Recurring themes, addressed in very different ways, keep re-appearing: the taken-for-grantedness of the everyday rural and urban environments that not only draw attention in time-honoured fashion to the potential in overlooked spaces, but which betray an underlying anxiety about the fragility of these spaces; the particularities of place; and the importance of place as a holder of memory are all present here. JUDITH STEWART |

||

Judith Stewart is an artist, writer and occasional curator whose work focuses on the role of culture within politics and the place of the political within a cultural work or event. Committed to collaborative enterprises, her curatorial work developed in order to provide a space where some of the questions raised in this area can be tested more comprehensively than is possible through individual practice. |

||